FarAboveAll - The Textual Question

Introduction

How good is the translation of your Bible? In particular:

- From which manuscripts was the ‘original’ text taken? The issue is particularly

relevant to the Greek of the New Testament.

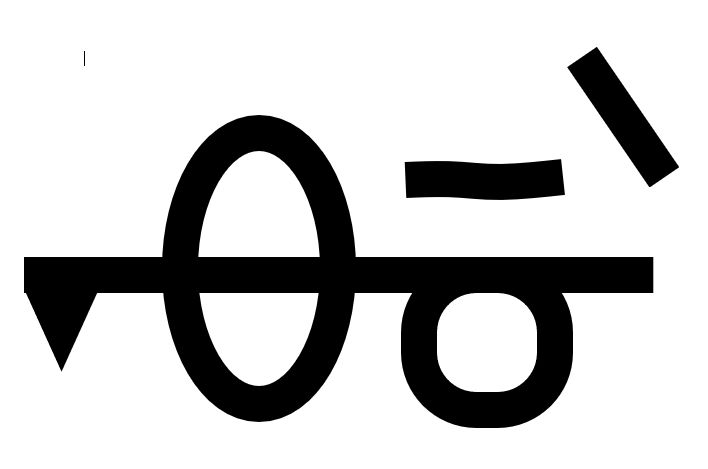

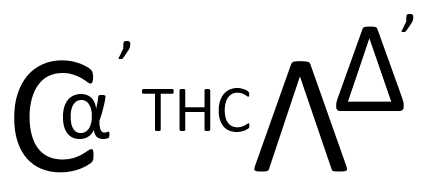

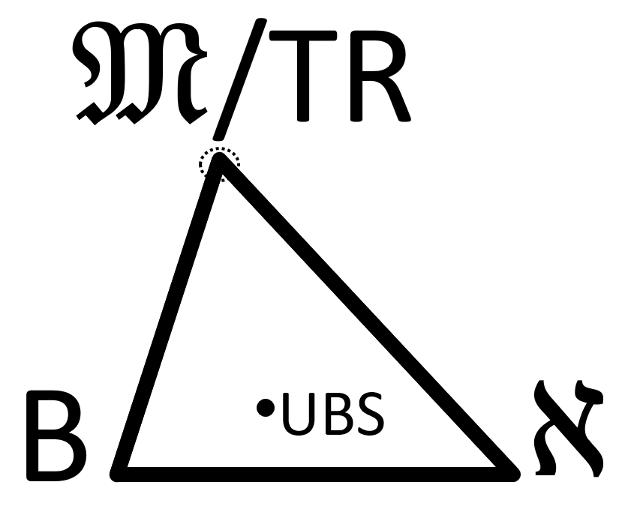

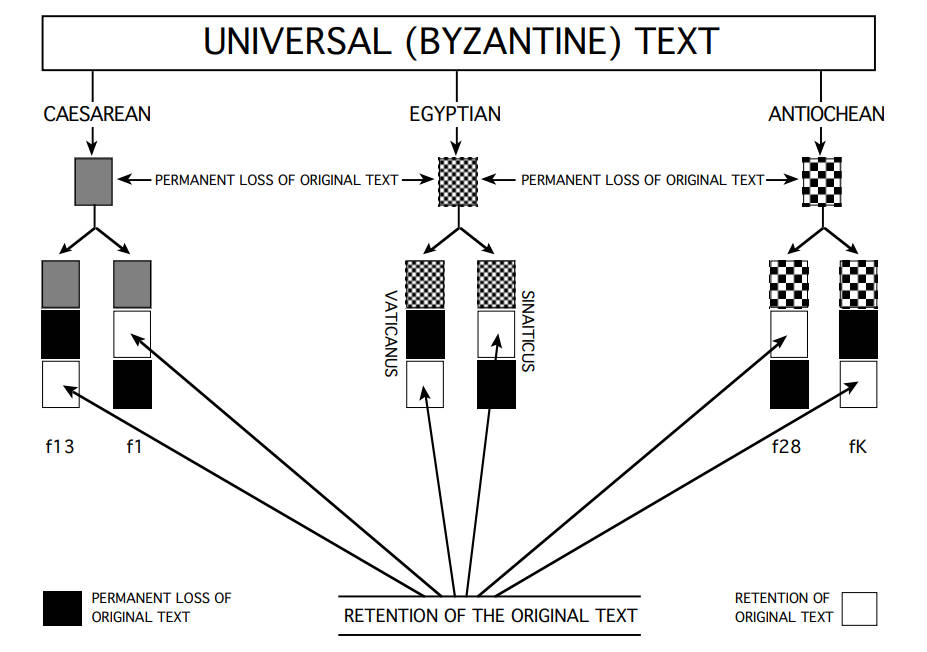

- The minority Egyptian manuscripts are the basis of texts in vogue for so many modern translations. One such text is the Westcott and Hort text, on which the Revised Version was based. The latest such Greek text is known as the Nestle-Aland 28 / United Bible Societies text. These Egyptian manuscripts often differ considerably among themselves.

- The Majority Text is the solid consensus of hundreds of manuscripts. Although the oldest of these manuscripts are not quite as old as the two oldest Egyptian ones, the Majority Text is supported by various church fathers and early translations (especially the Syriac Peshitto, which is traditionally dated as 150 A.D.) which are earlier than the Egyptian manuscripts. Moreover, this text enjoys widespread coverage in time and space - it spans all centuries and all parts of Christendom. We know of two editions representing the Majority Text: The Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text by Hodges and Farstad, and The New Testament in the Original Greek, Byzantine Textform 2005 by Robinson and Pierpont. The latter has the advantage that it can be freely copied, and it is the basis of our own translations.

- The Received Text is a text prepared by Erasmus in 1516 from ordinary manuscripts that were at hand, and as might be expected, it corresponds closely, but not precisely, to the Majority Text. It underlies the Authorized (King James) Version.

- The Greek Orthodox Church Patriarchal Text of 1904 also corresponds closely, but not precisely, to the Majority Text.

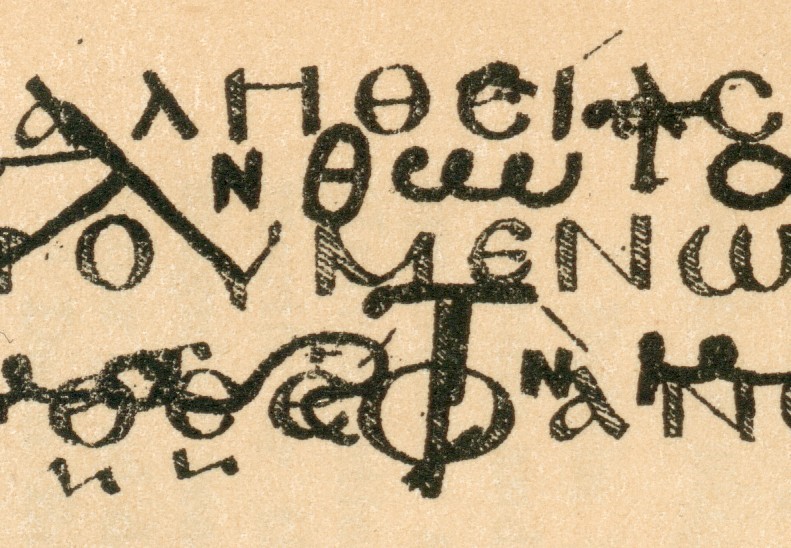

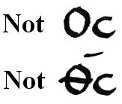

- How do we read the manuscripts? Do we accept it without question when, for example, we are told by some that a line in a theta is a later mark-up, or that a particular passage is not genuine?

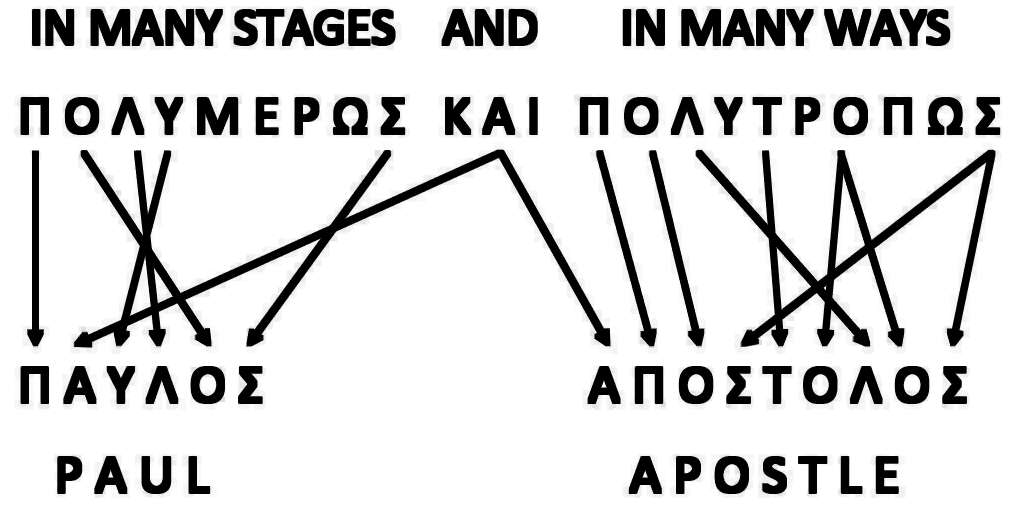

- How do we translate? We feel that a translation should aim to be reversible, so if a scholar were asked to translate back into the original language, he or she would come up with something practically identical to the original text.

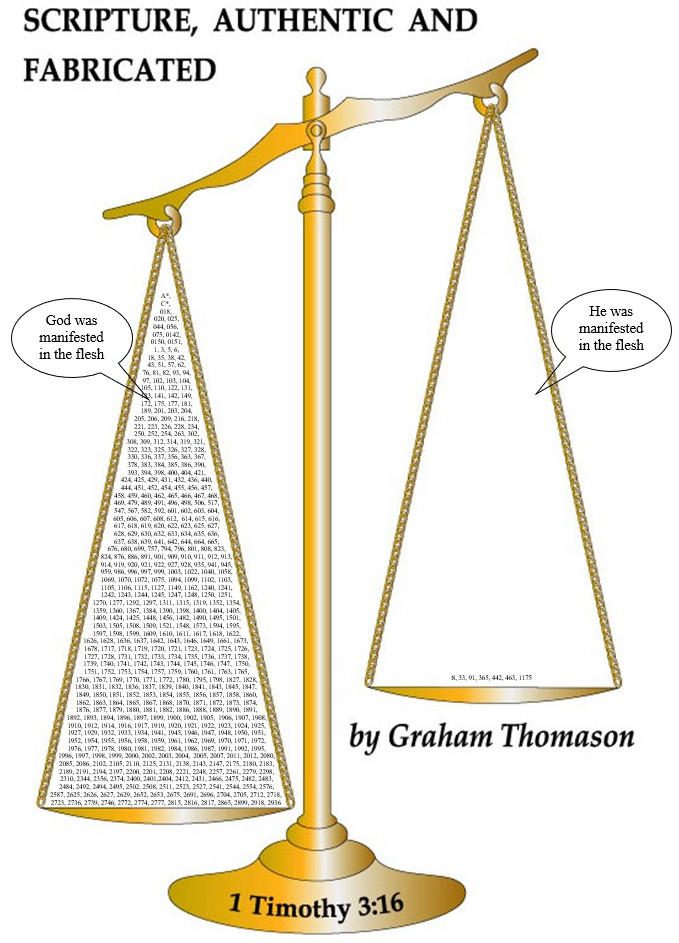

A good quick test of whether you have a good Bible is to look at 1 Timothy 3:16. If it reads God was manifest in the flesh, then you very probably have a good translation based on the Majority or Received Text. If it reads He was manifest in the flesh, then your translation is not based on the Majority or Received Text. If it reads e.g. Christ came in a body, then it is not a translation of any manuscript at all, and is just the result of someone fooling around on holy ground. Without God was manifest in the flesh, the Christian has been robbed of a rare and precious statement of perhaps the most tremendous truth in the Bible, that his Saviour Who walked this earth as a man and gave His life for him, is in fact a manifestation of God! In our studies (see below) we give dozens of examples of harmful corruptions in so many modern Bible translations.

We commend our own translation to you, available on this website here. We also recognize the value of the King James (Authorized) Version, or if you really cannot cope with its archaic, (but very worthy and beautiful) language, then the New King James Version. Don't be afraid to mark up your Bible with notes, - including textual ones, because it is possible to make a few (mostly minor) textual or translation improvements. Wide-margin Bibles are useful here. Another translation of the Received Text is the literal translation in Jay P Green's Interlinear Greek-English New Testament.

Textual Studies

These are less than 4MB unless otherwise indicated

Recommended Reading

- The Revision Revised by John William Burgon (1813-1888), republished by Dean Burgon Society Press, ISBN 1-888328-01-0

- The Last Twelve Verses of Mark by John William Burgon, republished by Dean Burgon Society Press, ISBN 1-888328-00-2

- Other books by Burgon:

- The Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels

- Causes of Corruption in the Traditional Text

- Inspiration and Interpretation (an earlier book, not on textual criticism, but excellently defending the Bible as the word of God, not the word of man).

- A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament (in 2 volumes) by Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener (1813-1891), published by George Bell and Sons, London, 1894.